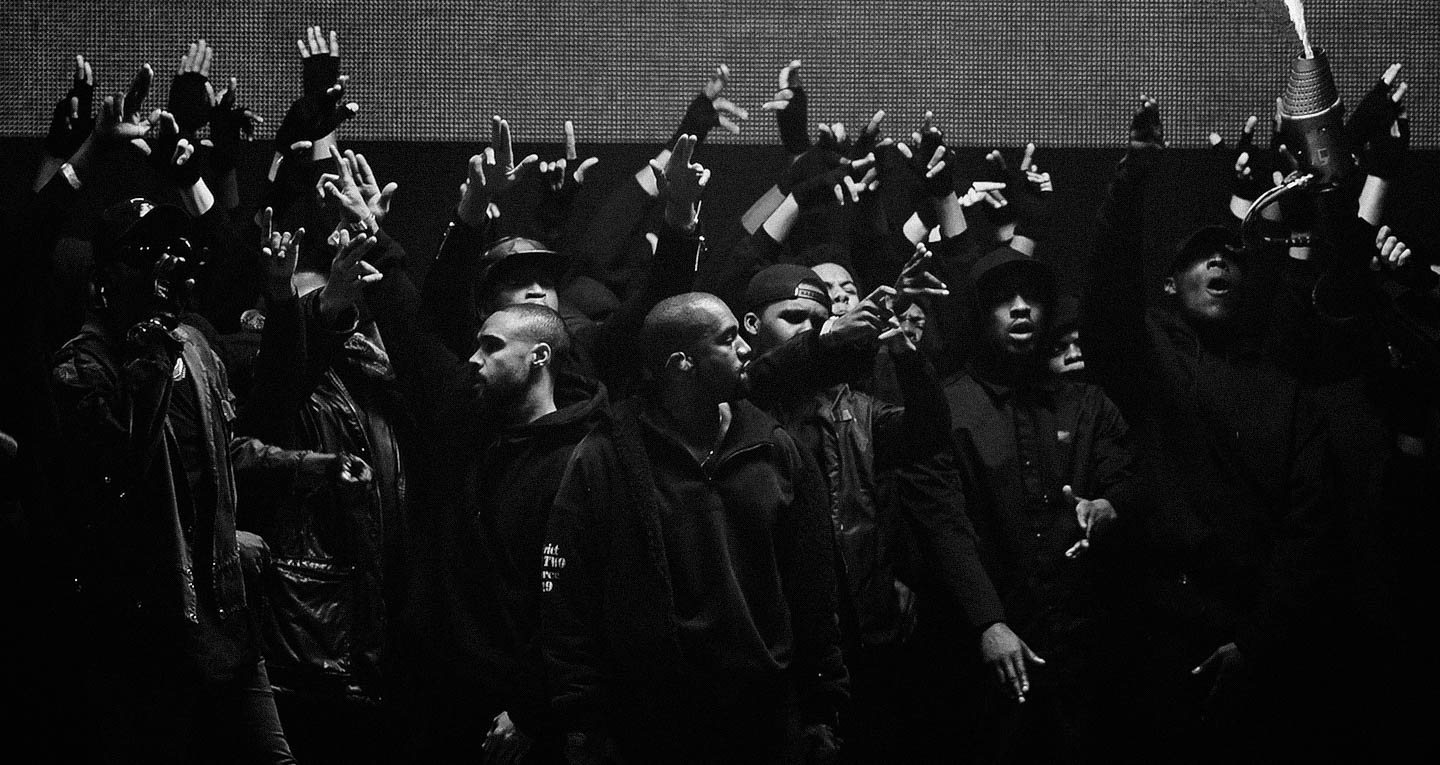

SWISH. This discussion serves as a celebration of all that we know, all that we love and, of course, all that we debate about Kanye Omari West. It started as a roundtable discussion through direct messages on Twitter between the two of us because we hated everyone else’s opinions. While that was (maybe) a joke, there was a real desire to talk about the influence, development and contextual significance of Kanye West on both our lives, and to attempt to explain the impact he has on people of colour, speaking from two different, individual diasporic standpoints. We also talk on the gaze and subsequent expectations placed on black artists who gain critical acclaim and global success. This inevitably leads us to discuss the progression and undeniable talent of a certain Earl Sweatshirt who we both rate very highly. People talking shit but when the shit hit the fan…

Amani: It’s safe to say that I’m an unashamed Kanye stan. I’ve been listening to his discography all morning for the purpose of this discussion and am amazed at how many feels I have every time I listen to the same songs that, in some cases, I feel like I’ve had in my iTunes library for my entire life. There’s a specific Kanye Effect™ that I can’t articulate to people who don’t get it instinctively, and it’s a much stronger feeling that I have in relation to many other celebrities I love and adore. In many ways, I feel like Kanye had his growing pains — and continues to struggle through them — for the both of us. That sort of affirmation of not having your shit together but also not giving into feelings of embarrassment is something really necessary to me. Kanye is important to me on many levels and I can only hope that we do him a little bit of justice, both in this discussion and in our day-to-day documentation on one of our greats. What are your initial thoughts when attempting to write about Yeezus?

Akash: Kanye was probably the reason I started writing. He’s such an integral part of our lives that he, and primarily, most importantly, his music serve as reference points throughout his life and the lives of his fans. Used loosely, he’s a day-to-day reference point for ideas, ideals, values that are relatable to so many things, more so than other artists who mean a lot to me. I wouldn’t be lying to say one of the quickest ways to learn a lot about someone in a small amount of time, is to ask them what they think of Kanye West… and they always have an answer! Everyone has an opinion of him, and whether or not they choose to talk about his music is something else entirely. I like how you mentioned his growing pains in that, not until very recently with being woke, a lot of people of colour on social media and in music criticism were hesitant to use it as an output, for what I now realise is a huge portion of my day-to-day thoughts and shared experiences. Now, as we are sharing these things, we’re becoming more comfortable with learning out in the open. It’s also true that Kanye has been doing this from day one and on a far bigger scale; that sense of strength that he presents when he is routinely singled out is important.

He has failed more times before College Dropout than people acknowledge, and more spectacularly than he ever lets on. It’s this sense of, yes, it’s absolutely fine to make these mistakes. ‘To be kicked on the ground and to decide that you can’t stand up again but whether you could take another kick by taking another risk.’ There is no one who takes as many artistic risks as Kanye does in the industry and to see it work out, seemingly every time, is what’s so compelling. In many ways I think that when I defend Kanye, it’s that I’m defending him as a person and all that he imparted on everyone listening throughout the years. All that he communicated to us over a soulful chipmunk pitched osmosis, although this particular stylistic thumbprint is morphing in his recent productions. Do you have significant signposts within Kanye’s music that you most vividly remember taking notice?

Amani: I just pressed play on my iPod and heard the opening church claps of Kanye’s “Power”. My favourite album of all-time is Late Registration and I proudly tote my broken copy like a badge of my love for the Louis Vuitton Don. In the endless list of personal favourites, “Power” ranks pretty high and is a song that I listen to whenever I need that boost of confidence or encouragement. The espresso, the battery in my back. Yes, yes, yes on everyone being late to the game: Kanye been doing this! I feel that’s often forgotten (or purposefully written out) in the time of the clapback, as we call out the bullshit of our particular disadvantages, both in the personal and the political, grander scheme of things. Kanye wasn’t necessarily the reason I started writing, but writing truth to people like Kanye was. A friend of mine and I regularly talk about Kanye, oscillating between laughter and tears because we realize our own (undesirable) characteristics in him. The loudness, the stubbornness, the ways in which we’re expected to keep a face of strength even in moments of grief, loss and high emotions, our seemingly contradictory pride and vulnerability. The thing about Kanye is that people assume his fans are erratic loudmouths — and if we’re keeping it all the way real, I definitely can be — but don’t understand how deeply relatable he is for someone like me, the young black kid with too many opinions.

I’m a black immigrant girl from Toronto, but still find myself screaming along to the grimy lyrics of “Crack Music”, where he coolly sticks it to racist American government policies whose aftershocks can be felt globally. I tear up as I whisper along the opening verse of “Heard ‘Em Say”. I smile when I remember his sweet ode to his grandparents, aunties, and of course, his biggest love and inspiration, the late Dr. Donda West in “Roses”. I’ve written a ridiculous amount of papers to the opening tease of “Can’t Tell Me Nothing”. A lot of how Kanye switches between widely understood and practiced black family values and allegiances (“Hey Mama”, “Family Business”) to the struggle to find work and gain higher education as a young black person (“Spaceship”, “School Spirit”) to simply stuntin’ on a hater (too many to list; my favourite subgenre) speaks really true to me. What I’m trying to say is this: when we as fans support (or as some would say, reissue his motivational speeches,) what we are essentially doing is reinforcing our own similarities to him. I can’t think of many celebrities whose critics elicit that type of frustration and loyalty in me, especially during times of Yeezy disappointment. Talk to me about that. Also, goddamn, how did I forget how fire emoji Good Fridays were? #BLESSED.

Akash: Incidentally, I like how “So Appalled” (A Good Friday track) is his favourite off of My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy; Pusha’s self proclaimed best verse is on there too. Late Registration was particularly interesting in that it signposted what I think was the point in which he decided to set out to primarily create pop music, as opposed to hip-hop. Graduation is, how he says at the start of “Big Brother”, more “stadium status” than the previous two albums and mixtapes. He vehemently states that he creates pop these days, I think the idea that he wants to create fashion that’s accessible to everyone as much as possible has its basis on the freedom in which creating pop music gives him. Labelling something as hip-hop immediately puts connotations and expectations from fans who are, let’s face it, are thirsty for a time that they don’t remember properly.

Back to fashion. He has this catch 22 where he wants to make everything ‘realistically priced’ where he doesn’t subtract quality. Fresh off a few days where I’ve listened to the Kanye lecture a couple times, I came across an excellent piece on how, despite these honorary degrees are handed out like Ello invites were, Kanye was vilified and ostracised for his acceptance of one. Saying he is the ‘wrong type of person’ to receive a degree is peak Kanye critique. He speaks truth to his predicament as he says in his lecture: ‘stepping from the immediate battle, to win an overall war, and to understand how long the war really is, understanding exactly how much to push…’ I think gives a sense of his awareness these days, along with the added responsibility of North, he wants to get away with as much as he can, but realises the limitations in which he needs to remain within in order to reach as many people as possible. Tough job.

Being a part of the (desi) UK diaspora, we tend to latch onto things in art that give a vague sense of home, seeing as we don’t tend to wholly belong to any area. An example of this is our slang, if someone uses slang from that area, gives a sense of home, you know? It’s just one of the few things including fashion and of course music. Grime and Bhangra/Garage were the immediate examples that come to mind, but as is the nature of things within the UK we sometimes look several horizons across the pond to the US, and in my particular experience that’s what happened with Kanye. Every record was released at just the right time when I needed it. Every record, along with the motivational speeches, are rich with bars and slogans that are concise, memorable and crucially be applied to those who are in some way oppressed. Even a few to those that aren’t, but if there were a scatter graph to show how many could be felt per person, the number would be on a negative correlation, starting with the most for black people, to brown, and then to white. I could never say that the statements mean the same amount, I assume not, but at the same time I know how much it does to me. That’s how I respect that boundary, not just with Kanye but with a lot of the art I consume. I’m always thinking about this, and how best to convey it but right now, at this moment in time, that’s what I’m going with.

Something else from the lecture that I will be quoting in every conversation I have in the upcoming weeks, including compromised chat with coffee baristas is the complimentary contradiction of two Yeezy statements: ‘the idea of becoming an adult is the idea of conforming and compromising’ vs ‘I still won’t grow up, I’m a grown ass kid’ from “Through the Wire”.

His values haven’t changed through his life experiences so I think that’s why those who have liked Kanye from the beginning have stuck around. Those that say they liked College Dropout don’t realise those themes are still there in recent work, just a different sense of direction. His love for Donda & extended family is now growingly presented to Kim and Nori. “Family Business” can be applied throughout. What are your favourite bars and why?

Amani: Whew. You just said a few words. Whenever I interrogate why it is that I love Kanye so much, I always come back to some personal classics: “Roses”, “Family Business”, “Gone” to name a few, and Late Registration as a whole project, as previously mentioned. An old friend and I had both went through a lot of personal upheaval during the time of his sophomore release, and much of my connection to that particular album is very sentimental. Kanye was going through the shits then too. Our experiences of loss and grief were obviously different, but we shared a grounding sameness, no matter how arbitrary. You didn’t have to be a superstar to feel like you were letting down a mentor, as depicted in “Wake Up, Mr. West”. You didn’t need to have a PhD to learn that people would come and go ‘like seasons, and everything that happened was for a reason’, both temporal and in permanence. And yet, he showed out. He reminded us to “Drive Slow” and to appreciate our loud, sometimes overwhelming ‘auntie teams’, to think outside of our immediate situations and reassess our definitions of wealth in “Diamonds…” before enlisting the opulent Mr. Carter to take it one step further. One of the reasons Late Registration is so near and dear to me is because it is intensely therapeutic to listen to: you can cry, laugh and roll your eyes at Kanye’s ludicrously slick mouth and feel like you just had a heart-to-heart with someone who understands. And that’s what captures his whole allure: in his many ups and downs, he gets it. Or at least, we feel like he does. Kanye has been his own producer, his own poet, his own hype man and his own PR team, and has set the tone for an entire generation to follow, strengthening the resolve of young artists with a simple, reassuring mantra: ‘Laaaaa, laaaa, la la: wait ‘til I get my money right.’

In terms of signposted songs, I can only speak to the visceral way that my favourites from Kanye’s catalogue make me react. “Family Business” has always felt like an intimate monologue to me. To be black in America — or by extension, in Canada, the U.K., any of the countless homes of the African diaspora — is to be scrutinized by your respective legal system and to know loss at its hands. Speaking of incarcerated family members or friends or exes or neighbours is a conversation that can sometimes feel like a monotonous, yet heavy anvil to your spirit. What I love most about this track is that Kanye subverts the solitude of prison, enlisting the images of his large and unapologetically black family as they help each other heal through monkey bread, polaroids, and embarrassing memories of childhood in low-income homes. It’s songs like “Family Business” that make me want to scream when critics say that Kanye is out-of-touch; these sentiments are echoed in “Gorgeous” and in Kanye’s unrelenting display of confidence in his abilities and the potential of all who surround him. To speak to mass incarceration of black individuals as a communal punishment of all who love them, by insisting that there are those who love them and support them is so vital. To refuse our imposed criminality, either by practice or by association is necessary. I can’t pick a favourite bar: all four minutes and thirty-nine seconds serve as an exhale for those who can relate, melodically singing through our pain and, more importantly, our resilience.

Akash: On the subject of new Kanye, A$AP Rocky released “Jukebox Joints”, produced by Yeezus, featuring Yeezus. The second half of the song, the instrumental is a slowed down version of “Love It Here” by Elzhi, produced by J. Dilla. An ideal example of what you were just referring to is Kanye’s amazing last line: “they tryna throw me in a white jail cause I’m a black man with confidence of a white male”. More and more, with each passing production credit on a song in 2015, it seems like he’s going back to soul samples, and intentionally not pitching them up either. “IDFWU” & “Sanctified” being the two massive examples of this return to what some would call his ‘golden era’. In terms of tone I think the new album going to be more like Graduation than any other, simply because Graduation was his most pop sounding sonically, his quotes about ‘summer cookout music’, admitting Drake beat him in the year of 2013 with NWTS, in terms of popularity and sales, and the aforementioned constant referencing of switching gears to pop rather than hip-hop.

Which brings us, somehow, completely unrelated, to Earl Sweatshirt. I was too young to see how Nas grew up from Illmatic onwards, but with Earl, we’ve witnessed him growing up more so than any other artist of his talented level. I’m purposely not going to refer to the ‘exile’, as writers tend to focus on that a suspicious amount. Lyrically, he’s grown up a lot. Those who judge him on his past lyrics are doing him a disservice, just as though who do so regarding Kanye. His wordplay is unparalleled at times: a steady drawl, no rushing, each word alloys into the next like molten chrome. I know you rate him very highly so what are your immediate thoughts about Earl that you want to share?

Amani: It’s kind of funny to me that every Yeezy feature of 2015 has been relatively weak, yet he’s shined on both “Only One” and “All Day”. I find myself always bypassing his verse on “Blessings” and, though I appreciate ASAP’s latest effort way more than I thought I would, Kanye’s verse gives me the “Celebration” type eyeroll and laugh. Either way, as I’m sure you know, the excitement of “So Help Me God” — no, I’m not accepting the new title — is very, very real.

Young Thebe is a special one. Like I said earlier, I think that Kanye’s career has inspired an entire generation of creative kids, myself included. Earl’s braggadocio makes me smile, and I truly believe he’s a burgeoning genius making his own lane with no time for the bullshit. I respect that. He’s calculating and, not unlike Kanye, holds no reservations about making mistakes in the open. I do think, though, that comparing them isn’t as useful as assessing them both for what they are: we’ve been able to see Kanye progress for eleven years and counting, a fully grown man, father and husband in his own right. Thebe has just turned twenty-one, and has a story entirely his own, with very different relationships to the come up, friends and family and, ultimately, the spotlight. It’s because of this disparity that I find him so fascinating: where is he going to go next? How will he write his story?

In such a whirlwind of a relatively young career, Earl has no interest in proving himself to anyone other than himself and those who he’s let into his close inner circle. I completely agree with what you touched on re: the fixation of his ‘exile’; it’s unfair and dishonest to his many accomplishments to continue to focus on the fuck ups of a sixteen year old and his intensely private recovery. I’ll say it again: he’s an incredibly smart kid who’s been forced to experience some of the most formative years of his life under the extremely entitled white, suburban gaze of the Odd Future following, who have held no punches in publicly stalking both Thebe and his mother under the guise of fandom. And he’s still emerged, a young black man invested understanding his specific and glaringly woke state-of-mind. It’s a miracle when you sit with that reality and all that it encompasses. Earl’s presence as a deft lyricist as well as producer is one that is unique in its manifestation. Of course, he has his peers: Vince Staples, Tink, Mick Jenkins, Noname Gypsy, Chance, SZA, a bountiful roster of young black musicians and artists of Tumblr and Soundcloud fame, but the space he takes up is noticeably unique, and I think that he’s more aware of that than any of us are.

His appearances on NPR’s Mic Check are my absolute favourite. Ali Shaheed believes in Thebe as much as I do, and their conversations show the magnitude of conversations not just between generations of black artists, but between contexts of what their occupation entails, the responsibilities they have, and the ways in which they take back some of that gaze and repurpose it for their own creation. I heavily fucks with their dialogue, and so does Earl: he’s said that it was the one place where he felt that he got the most across. That’s big for someone as contemplative and thoughtful as Thebe. It also opens up this discussion of how much stress do we as listeners, fans, and haters place on the (young) black people who are still trying to find their truths? How much do we expect and how much do we consume?

Akash: There is something about Earl’s aura that comes across as wiseness beyond his years. Something that was not present in the early OF days, though it’s known that people of colour reach adulthood in the eyes of the public faster than our white counterparts. But, if you look closely, as you said, he’s more aware of the space he takes up now more than ever. He’s grown up fast. The expectation of what we put on these artists, through our own gaze is inherently difficult to maintain, once you’re aware of what you’re doing. We want them to fit what we need from them, and nothing else. We need to do better. A recent tweet by Thebe has been cascading in my head for days, I’ll go fetch it.

“there’s way more depth to my character than just #sadguy tho don’t play me or yourself by attaching a fleeting emotion 2 my permanent person”

That’s self-confidence and an understanding on a platform which demands people stay in their lane, by simply stating what we all know about us all being extraordinarily complex creatures of habit. Media platforms in order to form a narrative will fixate on something, for example, his new album title, I Don’t Like Shit, I Don’t Go Outside. Forming an album review with that as the angle seems almost too easy. Something about Earl’s music is lathered in idiosyncracy, and it demands you pay attention.

I remember when he arrived back from camp and just how shy he was on stage, I can’t say for sure it seemed like he was almost embarrassed of his own talent? (He probably won’t like me assuming things.) An example of this is the “Oldie” video, a impromptu party during a photo shoot that sums up the OF movement at their peak; it would end up as the music video, Tyler naturally conducting, pulling people into frame when it’s their turn to rap. When Earl’s passed the mic, his verse is easily twice as long as anyone else’s, he tries to stop, you can see the myriad of gears in his brain working as he tries to remember the lyrics he created in many moments of creative alchemy. I can’t say for sure, but I really don’t think he has his peers when it comes to wordplay. Chief Keef, Durk, Sicko Mobb, they all share similar talent levels and age to Earl, but Earl relies a lot more in his lyrics to get his emotion across. His words rather than how he chooses to export them to the public. In terms of voice morphing it’s a pitched down growl, his and Tyler’s signature from the jump, but we’re acclimatised to it.

“Gorgeous, chrome plated horse-whip” is a line from “Hoarse”, easily my favourite song of his, with Frankie on the hook. It’s pitched down, but it’s him. Earl over a slow ass guitar? We’d see this again in “Faucet”. Something about him being over these rumbling strings, or ropes? Boxing ring ropes that his voice bounces off. I like how well he gets across images of brokenness or beyond repair. “Look who’s as useless as a broken wrist when tryna open shit / Sweeping up the glass to use it as a garnish over tracks damaged like the leg he limping to the barn with..” As if through the course of the track, his voice and legs suffered injury, cut to the bone, and is still travelling through a sandstorm, burning sand getting stuck in an open wound; an image Earl could easily come up with.

With Thebe just having releasing an LP, we’ve got a decent amount of time to mull over our thoughts until the next record. Skepta confirmed at his RBMA that he’s definitely on “Konnichiwa”, his highly anticipated album. Other than Frankie, who he collabs with on a Kanye and Twista circa 2008 level, he doesn’t do many guest features. MF Doom and Flying Lotus were first to voice admirations for Earl’s talent, he seems to only feature on tracks where there is mutual respect, which is hella reassuring. With Kanye, however, a likely summer release is just around the corner. How he uses the gaze of the media and public to create his new record will provide us with more music to lean on like the glass window of a nightbus. Even if it ends up being as ‘weak’ as Graduation, it’ll most likely have at least one “Flashing Lights” level song on it. Could you elaborate on your final points a bit more?

Amani: I think that what this discussion has been getting at is the reach and breadth of black artists to their black audiences, as well non-black people of colour, namely Mister West, Mister Fresh, Mister By-Hisself-He-So-Impressed. It’s interesting that we went from talking about his influence to our favourite songs to the people who followed suit as they shed an innate desire to be liked, while still demanding love and recognition for their labour. It really speaks truth to the natural progression of the cyclical nature of critical acclaim. Kanye is, by no means the only artist who has ever received love and hate, often simultaneously, but to deny that he is an anomaly of our generation would be intellectually and culturally dishonest. It’s because of this that I bring up the Kanye Effect again: he’s set a tone of excellence that holds him accountable first and foremost, yet allows for fans and haters alike to get a look at the grittiness of what trial and error truly entails.

All of this isn’t to say that Kanye is faultless. He has his fair share of questionable quotes and his penchant for using his interracial relationship as a euphemism for the future of fusion is too optimistically inaccurate for me to stomach. Yet, I still believe in black artists taking the leeway that is served up to everyone but them. I believe in our potential, and I’m interested in seeing where he’s headed next. I think that his tentative album with Aubrey, collaboration with Skepta and endless influence on Thebe and his peers speaks louder than any essay ever could. Looking to black artists as more than singular icons, but as a continuum of valid and valuable creativity is a process worthy of study and analysis by the people who it affects most. SWISH.

love it, good read

Thank you both <3

y’all did the damn thing

Great read – thank you. I’m a huge Kanye fan and you’ve inspired me to really give Earl a chance; I haven’t listened to him yet, but will now.