Freedom To Spend is a label that takes unheard or underappreciated sounds from decades gone by and repackages and recontextualises them for a new audience. In recent years they have released music from Michele Mercure, Ernest Hood, Ursula K. Le Guin & Todd Barton, Pep Llopis and more. 2021 has seen the label release Tiziano Popoli, The Same, Uman and most recently, Pamela Z, as well as a compilation of the label’s output in conjunction with ostensible parent label Rvng Intl. and sibling Commend. We sat down with label founders Pete Swanson and Jed Bindeman while Jed was visiting Pete at his home in Los Angeles, and sought input from third member Matt Werth too. We discussed the runnings of the label, the joys and pitfalls of working with rare material, the plight of the vinyl industry and more.

First of all, how are things going? How are you both? It must be nice to be in each other’s company, I presume that hasn’t happened a lot.

Pete Swanson: “It’s great. I’m from Oregon, so the first trip I took, post-lockdown, was to visit my mom, and she’s up there so I got to see Jed a couple months ago, and it’s great to have him down here now. He’s probably the person I’ve seen the most outside of my wife, post-pandemic.”

What about you, Jed?

Jed Bindeman: “I am having a lot of intense moments on this trip just because I haven’t gone anywhere in like two years. Getting food, hanging out with old friends, I’m feeling really good right now. It’s a very much needed trip. Pete and I had a good listening session last night, just checking out a bunch of weird music.”

PS: “That’s typically what we do when we hang out, it’s like, listen to weird music, go record shopping, go buy more weird music and eat a bunch of food.”

That brings me on to my first question. What’s the process you go through when it comes to putting something out? Where does it start?

PS: “The whole label is almost entirely run on a text thread [laughs].”

JB: “Pete, Matt and I have a text thread, it’s been going, I mean, five, six years now. It’s just a never-ending avalanche of people being like “ya heard this? ya heard this?””

PS: “Yeah, it’s like “oh hey I found this tape, let me rip it for you, here’s the link”, you know, a lot of that and then things will eventually get more formal and end up in an email that has people from the RVNG team on it making sure to keep us on task.”

JB: “Which is definitely much needed.”

PS: “But really, it’s just socializing, [sharing] extremely obscure music with each other.”

Okay. That sounds like a lot of fun.

PS: “It’s great. It’s super fun.”

I suppose you wouldn’t really do it otherwise.

PS: “No. It’s a total blast, and for me, I was a pretty busy working musician for a while, and then I started this career working in mental health, and Jed and I had been talking about starting a label, but I really wanted to continue working with music. And I knew I wasn’t going to be able to take a bunch of time off or anything like that so it’s a really nice way for me to stay engaged in music culture.”

Sure, yeah. Can you elaborate on your non-musical work?

PS: “When I was in Yellow Swans, which is like, gosh, 20 years ago now, 15-to-20 years ago, jeese, Gabe [Saloman] and I, neither of us [had] really gone to college and we were just touring musicians. And we were able to make it work – it was pretty cheap to live in Portland at that time. And I would go back and forth between being on tour and working in a mental health context. I work a lot with people who are unhoused, people with developmental disabilities, things like that. And the last place I worked was this transitional housing program that was sort of like a residential hotel with services built into it. Most of the people who lived there were dealing with schizophrenia or severe bipolar disorder or severe PTSD, and some of them were dealing with substance abuse issues, and there was a history of chronic homelessness there. I just loved working in that context, and I went through this period where the band broke up and all these other things kind of fell apart in my life, my job, I went through some changes. So, I decided to go to college, and pursue that path a little bit more deeply. So ultimately, I ended up deciding to go kind of in a medical direction. I’m a psychiatric nurse practitioner now, there isn’t necessarily an equivalent outside of the US, but I have a master’s degree where I specialise in psychiatric medicine, and basically my job is to manage medication, I have prescriptive powers. I manage medication for people all day every day. So basically, I have this gig where I’m working in an outpatient clinic keeping people with mental illness stable. So, I love the work, it’s very fulfilling but it does not allow for me to go and do a two-month tour.”

But I suppose you seem to have moved in a more curatorial direction, doing things like radio shows and the label. Are you more interested in that side of music rather than performing and dare I say, creating?

PS: “I’ve always liked all angles of music. When I was a teenager in my tiny hometown, I put on shows and I would put out tapes for people, and it’s all kind of been a constant. So, now I’m not really making music these days because I don’t have the bandwidth, and it’s a little more complicated at this point, both logistically and, if I’m putting something out, I want it to be good, I want it to have meaning and purpose behind it, and I don’t really have the bandwidth to spend a bunch of time thinking about what I want to say, in that way. It’s a lot easier for me to wrap my head around working with Jed and Matt in this way. It kind of feels a bit like a band, throwing around all these ideas and the consensus is sort of where you end up, right? Sometimes someone will bring something to the table. And two of us will be like “Oh that’s where we should go”, the other person’s like, “I don’t think we need to continue down this path.” We were just talking about this classical record and Jed was kind of like, “I don’t know if we need to do like another minimalist record before we do some other stuff.””

JB: “I think it’s interesting that you and I, you know, we have different trajectories of how we came to where we are now, especially with our … I’ll put my job as a “career” in quotes because I have a record store, but I like I feel like Pete and I both stopped playing music as nearly as much around the same time, because I played drums, and I used to play in a lot of bands and put out a lot of records and tour and stuff as well. I still play the drums for myself, but I don’t play in bands anymore and have purposely put all that on the back burner to a large degree, and I feel like both of us, as people that are still musicians and identify as that, but also have prioritized the world of listening to music and discovering music and trying to introduce other people to things that they may not have heard before that we care about, getting a lot of joy out of that, we share that with each other and Matt as well. I know he stopped playing music, quite a long time ago, at least in terms of playing in bands or with other people.”

PS: “We’re fans first. The label is super collaborative, and we do a lot of delegation of responsibilities, but some projects are more owned by different members of the label.”

JB: “We’ve got an album where different people wrote different songs. Rather than just being like, this is the band of so-and-so, and they write all the songs the other people are helping arrange it, it’s true, each one of us has kind of brought different projects to the table and sort of like, you know, once they’re brought to the table, everybody is involved but you know, there’s different things that have been passion projects of each of us as individuals.”

Like whose baby is this one in particular.

PS: “Yeah, totally. We’ve done a couple projects where we have to kind of cobble together a narrative, out of a bunch of disparate tracks and there’s a lot of like, “Who’s gonna take on this editing project to deal with 10 hours of transferred reels. How do we turn this into an album?””

JB: “Who’s gonna talk to the family or the individual. Some people need a little more attention than others, and that’s totally fine.”

How much work do you have to put in, in terms of convincing people to go along with the project?

JB: “Some don’t need any convincing, you know, just send them an email, “here’s our idea” and they’re like, “hell yeah”, which is ideal. But then some, they very much don’t want to do it and no matter how much you try to, you don’t want to convince somebody because you don’t want to try and push them into a corner and make them feel like they have to do something, definitely, you’ve got to finesse things. But some people no matter how much you try to finesse it they’re just not interested.”

PS: “Right, and you know, our deal with artists is pretty fair, it’s pretty straight-up, there’s not a lot of crap.”

Because at the end of the day, it’s their music of course.

PS: “Yeah, but also, it’s kind of wild for us to be these people coming out of nowhere being like “hey, you know this tape that you put 25 copies out of in like, 1986, this is the one, we’re gonna press this, we’re gonna blow it up”.”

JB: “Especially for people who are like: “I’ve been making music ever since then, that thing I made when I was like 19 years old. I don’t care about that. I don’t want anything to do with that. Here, listen to the stuff I’m making now.” And it’s like, how about we divert the conversation back to the old thing. We want to do that and they’re just like, “that’s not what I want to spend my time thinking about” and that’s fine.”

PS: “But that’s also just like the first hurdle. Like, Robert Cox. He is the kind of dude who, we contacted him, he had all the masters already set aside so yeah. Pamela Z, she had transfers of the original DATs that weren’t like brick wall, you know, that we could work with. There are some artists, where it’s just like everything’s there.”

JB: “And there’s ones where there’s nothing, or the things are there, but they’re not there just to pick up, like the Ernest Hood project. The family is based in Oregon, which is where I live, I was doing all of the in-person finagling with them, and it was awesome, but it was a lot of work and a lot of Pete coming to town, and us going to the family’s farm. It was lots and lots and lots and lots of work. In the end, I personally feel so proud of it, it was worth it. It’s awesome, man. It was, yeah it was a doozy.”

PS: “So, Ernest was an engineer for a community radio station in Portland, and we went to the family home that’s in what’s now Oregon wine country. And I came up for this trip because we knew that it was going to be a bit of an ordeal, and we were all going through like thousands and thousands of reel tapes, and a lot of them are just radio shows of spliced together mixes of jazz and stuff like that. So, we had to go through all this, trying to find master tapes. And it was just box after box after box of reels.”

And are you doing this in their property? You weren’t able to take it away?

PS: “It would have been too much for us to transport.”

JB: “It was a house full.”

PS: “Basically, three rooms full of reel-to-reel tape.”

JB: “Floor to ceiling boxes, yeah, I will not forget when you were looking, we’d been looking through so much stuff. We found a lot of really interesting unreleased recordings, but we were specifically looking for Neighborhoods, that’s why we were there, and to find what else, whatever else we could find along the way, but we needed Neighborhoods. And we were about to give up, the son, Tom, was like, “It’s here somewhere.” He was just sitting there hanging out, he was like “this is your thing, you guys deal with this”. But Pete’s digging through one of these boxes and he was like, “I found it!” It was the bottom box underneath piles and piles and piles of stuff.”

PS: “It was the last box in the last room.”

JB: “And it was in good shape! So much of the stuff was mouldy and unusable and that was not, thank God.”

PS: “And then later that week, we met up with Ernest’s son, and took the original reels, to the studio of the original engineer, and it had his handwriting, on, on the labels and everything.”

JB: “1974, a long time ago!”

PS: “So, we brought it back to the dude, we’re like, “Hey, do you still have this tape machine, can you transfer these. “Oh yeah, I think we I think we can.””

Yeah, that must be fun. I mean, once you get through all the slog.

JB: “But the slog is still fun, you know, it’s, it’s definitely feels like a like an archaeologist, excavating these things from the past and hoping that they’re usable.”

PS: “And you discover what’s there.”

JB: “It’s really fun.”

With the UMAN project, what was that like, because that’s obviously in a totally different continent, country.

PS: “That was entirely handled by Matt.”

JB: “In terms of different people handling different projects, that was a Matt project.”

PS: “We’ve been in the loop, a bit, but it’s a project that he had been socializing with them for quite a while. There are a couple of releases that we’ve done that Matt had originally planted the seeds for, like, 10 years ago. And UMAN, he’s been talking to for quite a while.”

Matt Werth: “I found an e-mail address for UMAN’s buried on a web site that hadn’t been updated by the group in, literally, a decade or two. Given the context, I thought the chances of receiving a response would be slim-to-none. Stubbornly, I followed up a few times over the span of two or three weeks, and out of the blue, received a response from Danielle seven months later.

“It took several more months for Danielle and Didier, her brother and the other half of UMAN, to warm up to the idea of reissuing Chaleur Humaine. As with some other artists we’ve worked with, UMAN had some experience working in the major label system, which left some unfortunate side-effects and distrust of terms. We’re obviously coming from a totally different place, so it’s second nature for us to treat those wounds and our artists with respect and care.

“Once we finalized our arrangement with Danielle and Didier, we moved quickly but considerately to assemble as many original sources to ensure Chaleur Humaine was elevated to the heights the album deserves. Fortunately, Danielle and Didier have continued to make music and art over the many years since Chaleur Humaine was released and had the great sense to keep their archives intact.

“We insist on working with original audio sources for FT$ reissues unless we’ve turned over every single stone and there is no other option than to use the “commercial” product. That severity has bitten us in the ass on occasion, and we’ve even abandoned projects because it, but it’s all in the service of the music and artist. Danielle and Didier were especially ecstatic with how everything turned out, which really meant the world.”

PS: “Vinyl production is way delayed right now. I think we have four other approved test pressings that we’re like, just sitting on. that’ll like be releases through probably fall of next year.”

Okay. And does that include Pamela Z?

PS: “Yeah. Pamela Z should be landing in the next couple weeks, like the vinyl should not be delayed.”

Well, obviously, you own a record store Jed, and you run a vinyl reissue label – given the sort of conversation around vinyl at the moment. how do you feel about this in a long-term sense if you don’t mind me asking?

JB: “I’ve been wrestling with that question; I mean my shop is all second-hand. I’m not really involved in the purchasing of new inventory, I’m one of these people that’s always going around trying to find collections of used records, at record shows and trying to find things that way. But it has been really interesting to see how the record buying and selling world has changed since COVID. Because it’s very different. When there was the major lockdown time last year when everybody was at home, not leaving the house for like three or four months, just a solid chunk of time, my shop was closed, like everybody’s shop, but my online sales were stronger than ever before. It was crazy. And since then, the price of so many records, things that for 20 years have cost $20 or $30, a lot of these records are now regularly selling for 50 or – Fleetwood Mac records sell for $50 on a regular basis. I’m not kidding, like Rumors is a $50 record.”

Aren’t there thousands upon thousands of them in existence?

JB: “Millions! Literally, millions. But people buy it, and I was like this is weird, it’s like, what’s happened? I don’t know how sustainable this is, at some point, the bubble that’s grown, the bubble’s getting big real fast with that world, and it has to burst at some point. And I don’t know what it will like when it does up, but, I run the shop with a friend of mine, and we purposely try to do the thing we do, and not really participate in that world of things, ’cause it just doesn’t feel sustainable, and it just feels kind of gross – $50 – no, Fleetwood Mac is not a $50 record, just ’cause it sells for that, it’s not a $50 record.”

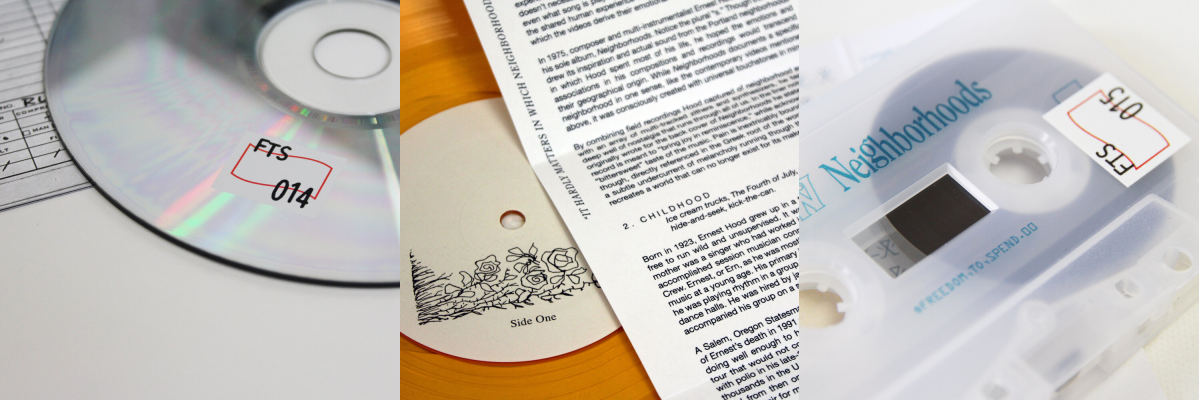

PS: “One of the things with our label though is that a lot of what we’re pulling from are cassette releases. You’re talking about this vinyl delay, and I’m still buying up new cassettes! That production turnaround is still really good. and we also have CDs. It seems like a lot of people are producing more CDs these days.”

JB: “You can get a CD made – I run another record label, aside from Freedom To Spend. And I’ve been thinking about the future releases I’m doing and looking at production times and costs and stuff like that, maybe I should do some CD runs because you can get a CD, turn quick turnaround in two weeks, or the exact same thing on vinyl is a year – (PS: “Or longer”) – or longer. I kind of want to get this music out there soon. There aren’t as many people that are buying CDs as there are records nowadays in this world, but more people are. For us in the world that we operate in with the reissue culture and world, people have been concentrating on finding music from the ’70s and ’80s, which came out on vinyl, and they started coming on a cassette in the ’80s, but now more people, us included, you just keep digging later, and now people are digging into the ’90s, so many things that only come out on CD. And a lot of really fantastic music to be discovered if you don’t compartmentalise like “I only buy records”. Well, you miss a lot of good music. The 2000s, with CDRs, there was fucking millions of these things that came out – a lot of it’s not great, but you can find some really cool stuff that’s just on CD.”

PS: “When’s somebody going to come along to pitch to you the Heavy Winged reissue?”

JB: “We’ll see! With Yellow Swans it’s already happening.”

PS: “Right now, I have this Yellow Swans reissue that is basically taking two years to press. We sent it off, did the whole mastering thing, got the test back. And the test sounded like garbage. We had to figure out where things went wrong. We had to get the record recut, and by the time it got recut the turnaround went from being November last year, for estimated landing date, to the middle of this year, to November this year, and now it’s going to be, maybe March next year.”

And was this a special anniversary?

PS: “No, it was the 10-year anniversary of Going Places when I started talking to Boomkat about doing a couple vinyl reissues. Gabe, my old bandmate and I, we had been working on this Bandcamp archive that we put on pause while we’re waiting for this record to get produced, for the time being we have like 50-some things up on the Bandcamp. There’s stuff there if you want to start digging. This double LP, it’s going to happen, and we’re going to put some more stuff out, but until that’s ready, things are on pause for a little bit. There’s not really much you can do. The only label that I know is having like good turnaround right now is Third Man.”

JB: “They have their own pressing plant!”

PS: “If you got your own pressing plant, you’re good. If you don’t, it’s going to take forever.”

JB: “It’s going to take forever for all like the obvious logistical reasons but also, talking about record shops and new labels and store labels and everything – I saw something online, about a Billy Joel 12xLP box set. It’s like, oh great! And they make 50,000 of these things.”

Record Store Day ruined everything.

JB: “It really just screwed anybody who’s not a huge label in terms of actually getting anything done. There are all sorts of reasons why other things are delayed but that just makes it so much worse.”

PS: “It’s compounded effects of COVID, more people are collecting records, more people are buying records. That means that major labels are pressing bigger and bigger numbers, there are also staffing issues and obviously shipping issues. There’s all of these changes and shipping and taxes and stuff like that. It’s going to make running record shops and selling things on Discogs just more complicated.”

JB: “I feel like a lot of people are turning to digital, in a place like Bandcamp. Especially if you’re looking at a release that you’re tempted by if it’s overseas and you factor in all of the costs, plus the shipping you’re like, I want to buy this record, but it’s going to cost me like $42. I’d love to have it, but the digital’s here, the band’s going to get the money. It cost me $8! Well, I guess I’ll do that. Bandcamp is a pretty amazing resource nowadays, it’s the way that people share and discover music.”

I’ve been using Bandcamp for more than a decade I absolutely love it. It’s almost too easy.

JB: “I know.”

I’m a big fan. I mean it’s so funny, you go to buy CD or vinyl or whatever and like, or even tape, and the shipping price is as much as, if not more than the thing you’re buying in first place. If you could just buy the digital, it’s right there.

PS: “That’s one of the things, working with Matt and the RVNG infrastructure is very helpful because they’re like, “Oh, how can we figure out fulfilment in Europe or in the UK?” They have all of these things that they are able to figure out logistics for, and it just makes the availability of the records so much easier. We’re actually working on a new series of releases that are going to be more limited, but when we’re doing the bigger freedom to spend releases, they’re able to get out there. If we put out or buy a band from France, or a band from Spain, or whatever – we did we put out that Pep Llopis record, I think he did an event at like a Fnac in Valencia, which is cool! It’s cool that they have the ability to reach out and deal with press in Spain.”

It’s not just ‘this American label put out my record and that’s it’, ‘my record is coming out and here it is’.

PS: “Yeah, and it’s everywhere as opposed to just here in the US.”

In terms of FT$ and ReRVNG, have you ever had any clashes along those lines? I know Matt doesn’t seem like a very confrontational sort of person from the outside, but have you ever come up against him and be like “no I want that for my label”, or is it just distinct enough that that never happens?

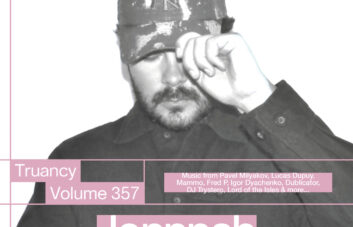

PS: “There are a couple ReRVNG and Freedom To Spend collaborative releases. We have that Michele Mercure collection, we had the Tiziano Popoli collection, and those are both releases that Jed and Matt and I all wanted to do that were collections. So, we’d piece together an album out of these like odds and ends from an artist, which isn’t really what we wanted to do with Freedom To Spend, with Freedom To Spend we wanted it to be more albums, or cohesive pieces of work. There are a couple things that we have in the works that are not going to be ReRVNG things that are cobbled together, they’re sort of anthologies, but there’s a certain cohesion.”

JB: “Also, the ReRVNG things traditionally, they’re usually double LPs, sprawling deep, you know, deep archive dig with a whole story being told behind it and it’s a very specific deliberate way of presentation and archiving.”

PS: “We do the label by consensus. So, there’s a lot of stuff that Matt wants to do on ReRVNG that Jed or I probably wouldn’t want to touch. Where our tastes overlap is the label and where they don’t overlap, Jed has his own label. Jed is more goth than Matt is.”

JB: “There’s not a goth bone in that man’s body!”

PS: “It’s true, it’s true.”

JB: “We do have a lot of similar tastes but all three of us also have very different tastes. I started my own label because there were projects that I had presented to Freedom To Spend which I kind of knew weren’t really going to fit into either of their tastes, or both, it has to be both of their tastes. So, when certain things were like that’s not really for me, I’m like, I get it so I’m going to start my own thing to do things that are for me.”

PS: “I feel like with Concentric Circles I can get kind of like go down the list and I’m like this, this is one that Matt nixed. This is one that Matt would say no to, this is one that I would say no.”

JB: “This is one you’ll both say no to.”

PS: “And then, you know, Matt does stuff that’s definitely not to my taste.”

JB: “That’s fine, you know that’s why people have their own different things.”

PS: “None of us are very territorial, it’s interesting working with Matt too because sometimes Matt will be like, “Oh, I’ve been talking to this person about a project,” and it’s like, “What label is this project for?” Sometimes he just has fingers in a reissue that ends up like on some other label. It’s something that he wanted to see happen but didn’t want to have under the umbrella of RVNG.”

So, something he wanted to do, and it didn’t really matter where it ended up but it’s more important that it happens.

PS: “Yeah, and Matt is always working on a million projects, and he knows everyone. So sometimes he’ll just be like “oh it’s really time for this thing to get a light shone on it”, he’ll kind of like socialize it, but it’s not linked to him. He’s kind of a man behind the curtain.”

Yeah, that’s nice.

PS: “Yeah, it is. But also, you know it’s really nice to see the ReRVNG stuff that he is really passionate about and see how he carries it through and does all the storytelling. It’s really great to be able to do some of that work with him.”

Tying in what you were saying about going from the ’60s and ’70s to the ’80s and then the ’90s. You mentioned the Neighborhoods project and how you were dealing with his son, with someone like Pamela Z who’s still alive, what’s it like dealing with someone who, it’s their thing as opposed to like their family thing? How do you find that conversation?

JB: “I feel like it’s ideal. Of course, it’s ideal with the artist still alive. You want to work with them and get their direct approval and their well wishes to go forward with the project. When you’re working with the family or whoever’s representing a deceased artist, it’s a lot to assume, maybe they wouldn’t like, but that’s not something you can really think about, because that’s not what’s happening.”

PS: “All the stuff that we’re working on, it’s almost entirely people who have worked fairly independently, they own the rights to their own music, they’ve been involved in the distribution and sales of their releases, they understand what the scope is, they understand what their music is going to make. And sometimes it’s a really difficult conversation to have with family members or it’s sort of like, we don’t know what this is going to be like, this is what the split of profits is going to look like, but we’re working with pretty obscure stuff, you know, a couple of our records have sold very well and done quite well. And we’ve been able to pay artists very well, but some of them have it. And if we go to an artist and we’re like, we love your work, we love this music. We really want to represent it. This is what we want to do, these are some of our releases, I feel like an artist will be like, oh, cool, you’re trying to do these releases at a pretty high value, with attention to detail, tell a story and blah blah blah blah blah. We’re really trying to respect the work and demonstrate our regard for the work and release it. And I think most artists get that, they understand the work behind the scenes. We’re going to make sure it’s cut really well. We’re going to make sure the record sounds good. We’re going to make sure it looks really good. We’re going to do press around it, we’re going to make sure it’s distributed, we’re going to work on syncs, we’re going to put that effort forth. The artists are like “cool, it’s awesome to like have somebody come to us and respect that and show our work the respect that it that it deserves”. Whereas going to the family, there’s this distance, maybe they haven’t worked in music, maybe they don’t know how production, distribution, things like that work necessarily. We have to sell them on the idea a little bit more, it’s a lot more fraught, because, when somebody is when you’re talking to somebody about representing their own legacy they can opt-in and opt-out, and it’s really direct and it’s one-to-one, and when you’re dealing with somebody’s estate, I think for the family, they’re always like, are we making the right choice here are we, honouring our family member in a way that’s respectful, and I think it’s a bit more complicated.”

JB: “It’s a little frustrating because there’s a few projects that were things that I found tapes that hardly exist – this will be like a private tape somebody made that I found at an estate sale or something like that, it’s like this is copy that I’ve ever heard of existing. A few things I have examples of, I won’t go into the details, really, really special music. And so, after doing some research, tracking down, oh, unfortunately this person died. Okay, I’ll get in touch with the next of kin. And there’s two projects in specific that were like, I can guarantee would be very loved and well received. But the family have zero interest whatsoever. Sometimes you can kind of tell that it’s like maybe their parent was like kind of eccentric or they were a freak in some way, and maybe the kids just never really understood the music they, it’s because it’s really weird. “That’s weird shit my dad made 30 years ago. Why do you want to do this, I don’t understand?” They don’t have any involvement in the music industry in any capacity. And they’re very wary, they’re just like, “Who are you, what do you want?” And so, then those projects are just done, and they are not going to happen, people get very emotionally involved, one thing was somebody’s partner, who passed away, so you’re talking to them and it’s a very emotional situation. Sometimes you try to work with it as much as you can, you try to be as gentle, but also really trying to push it along and they’re just like, “No, not going to happen.” It’s like, man, you don’t get it! And that’s the thing, people just don’t get it sometimes. There’s only so much you can do.”

PS: “Yeah, and a lot of times people have these ideas about what the thing that we should be representing is.”

JB: ““That’s not it, he would have wanted you to put this out.” Well, that’s not what we’re talking about, he’s not here to say what he wants.”

“I want to put this out!”

JB: “That’s the way it goes. But when you find an artist who’s alive and still has an interest in their music. That’s perfect.”

And has their DATs.

PS: “Some of these projects that we’re doing, it’s super easy. Pamela was awesome to work with. She’s super busy, she’s always working on performances, video pieces and stuff like that, she has a ton of stuff going on all the time, but she’s only put out three albums in more than 30 years.”

JB: “She is super badass and is on it, every step of the way, she is involved, and she is present and excited. So, it’s just been so fun and easy working with her.”

PS: “And it’s super straightforward, and it’s like, okay, we need artwork and she’s like, okay, give me a little bit and she goes and like digs up a couple things from her archives and sends us the things and it’s all organized and right there. And we’re not having to cobble together anything, it’s all just like “you need it. Okay, I’ll try and figure it out”. A week later we get what we need. And that’s great, but other projects we’ve done and it’s like, okay, we’re trying to find this one reel tape from the one person who may have it, and we have to find every single track individually. Some of this stuff, we work on a project and it takes its time and we end up with a finished product – sometimes it’s a year, year and a half turnaround. The Pamela Z thing is happening very quickly. But there are other projects that take years. We start it, we keep moving it forward as well as we can and hopefully, eventually it gets resolved.”

Do you have any dream projects that you’d love to do?

JB: “I mean we’ve all got wish lists”.

PS: “Every once in a while, we’ll be like okay what’s a white whale release we can chase, and we have one of those releases coming out, Neighborhoods was sort of like that.”

JB: “Definitely; I spent, I’m not exaggerating, years. Yeah. Before the contract was signed it was years of meeting up with the son and talking to him, over and over and over and over and over again, and not because he was a jerk, but because he works very slowly. It was complicated, it took a lot of time. some things just take a lot of time, and you learn over time working that some things you can’t rush, if you want them to happen and you want them to happen well. And for the people involved to be happy. You just need to let it play out. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t.”

PS: “But we have another white whale release coming out next year that we’re all super excited about, and it’s an artist that … yeah. it’s an artist that a lot of people don’t know.”

JB: “But it’s like… whoooh boy. It’s a special one.”

PS: “There was a comp that we all had, “oh these are like really great tracks on this comp”, and then like, we found a couple of the tracks and Jed found a couple other tracks and ultimately we were like oh we, we have like an album’s worth of material here! And we had heard through the grapevine that the musician was not into the idea of working with their old work.”

JB: “But people were wrong, because they were easy to work with and the coolest person and super excited. And it’s been a breeze. It’s taken some time, but the relationship is really healthy and fun. Like, wow, what a nice surprise.”

PS: “It’s awesome, but it came from this conversation where we’re like, what would be something that would be awesome to do that would be totally impossible.”

So never trust the grapevine then.

PS: “I mean never trust the grapevine, but I also think that there was some truth to it.”

JB: “They had had some rough experiences in the past that made them wary of the record industry.”

It just had to be done right.

PS: “Yeah, exactly. And you know, I think it all comes back to the importance of really respecting the art, and that’s where we all are coming from. We just love music, and there’s stuff that we are very enthusiastic about that we want to shine a light on. We try and be mindful about what we are bringing attention to and how we’re bringing attention to it, and I think that there’s a lot of music that got lost in the shuffle. A lot of the stuff that we’re pulling from is like ’80s DIY tape culture. Stuff that didn’t really get out there very much back in the day and it’s really like “oh, this thing is actually really significant, it does something that no other music that I’ve heard does. Let’s see if this becomes something bigger than it initially thought it could be”. And it’s fun to do that, it’s fun to throw things out into the world and be like, oh, people actually can sit with this wild, fake anthropological study of a people that didn’t exist, on its own! Originally it was only available with the novel, and it’s interesting to see it divorced from that and just presented as an album of music. And people really connected to it. Even though it’s like a record with a bunch of poetry in a language that doesn’t exist.”

Obviously it helps that it’s really good. If it was all of those things that you just described, but the music was terrible, then nobody would care.

PS: “Exactly that’s it, it’s. We’re just trying to put out great music, and we don’t always know what’s really going to click, the Ursula Le Guin record really took off, and it’s extremely good and it’s extremely weird.”

Do you think that in the 2050s, people are going to go through Bandcamp archives and find some lost and forgotten ambient release, that was lost in the sauce?

JB: “Oh yeah, without a doubt.”

PS: “I’m trying to keep up with what’s going on, there are all these ways to discover new music on Bandcamp. It’s funny, I get those emails about what my friends are buying, “Oh, what’s this,” and I’ll check it out, and then like I follow Common Time, which I think is a really good email list that compiles a bunch of very obscure stuff on Bandcamp, which is just a great resource, and some of this stuff is very very very deep and very obscure. The whole thing about ’80s DIY type culture was that it was this period where the means of creation were totally democratised very abruptly, all of a sudden you could have a studio, a pretty complex, professional-ish studio in your house, in a price range, that was attainable, and you could reproduce tapes, in small numbers, and that’s what people did, and with Bandcamp that’s just taking a step further, it’s great being able to talk to people who are producing pretty weird music and self-releasing music, from Africa, or Indonesia or Eastern Europe. Unfortunately, I feel the promise of the internet and socialized music is still very focused on big international pop stars, it’s all America, Western Europe.”

Even if you look at Bandcamp, one of the things that they have is ‘search by location’, but it’s still major cities across the US, and a couple of places in Europe. I think there may be one for Dublin, I’m not even sure, but it’s very hard to look for anywhere in Africa/South America/Asia. So, the promise of the internet, it’s not just big pop stars no matter how small you go there’s still going to be like a ladder of sorts that you have to negotiate. But we live in hope.

PS: “Yeah, and I mean there are steps being taken to address that. Yeah, I’ve seen a bunch of people passing around this Eastern Bloc database.”

Yeah, I was just looking at that the other day.

PS: “And it’s missing a ton of stuff.”

It’s very very new, it’s so new.

PS: “But it’s so cool because I’ve been digging further and further into that world of music, picking up records on Melodia and Jed and I both got really obsessed with NSRD after the Stroom reissue. So, we sought out tapes. I think one of the things that links all of us, me, Jed and Matt, is we’re all still really driven to discover new music, and to find cool new stuff. In the case of NSRD obviously Stroom started that. But we wanted to go in a little bit deeper and see what else was there, and there’s a lot there, there’s a lot of very good stuff.”

JB: “What’s so fun about doing this type of thing is that, usually there’s a lot of stuff. Usually with an artist you’re interested in, you decide to spend more time, especially if you’re an obsessive nerd like we are, and you go real deep, or you contact the artist: “What else did you record? what else did you never release?” There’s always more.”

There’s always a rabbit hole to go to down.

JB: “Yeah, and sometimes it can be so incredibly rewarding when that rabbit hole really connects with you as an individual. You’re just like, “Oh my god, what is this? No one’s ever heard this? You just recorded this and put it on a shelf? All right, let’s talk.””

PS: “That was the whole thing with that Tiziana Popoli collection, I reached out to him about deadstock copies of his old records. And I was like do you have any like archives? He just started sending us files and they just keep coming in, and it’s just transfers of reels after transfers of reels, and we ended up with so much material and none of it had ever been heard!”

That’s a very privileged position for you to be in, to be able to share it with the world.

JB: “It feels good.”

PS: “Yeah, it’s super exciting and it’s fun to be able to work with them to create a cohesive thing. I feel like most of our releases, as the pieces come together, there’s a certain resonance with the images and the liner notes and things like that. And when it really starts clicking together … it’s like a feeling, this intangible thing, “Oh this is coming together. And it’s right.” Sometimes it takes a little while to find the right liner notes or to find the right cover art, but we just keep plugging away at it until it’s good. Until it feels good.”

* * *

Freedom To Spend: Website, Instagram, Bandcamp

Images courtesy of the label:

Uman – Chaleur Humaine album artwork

Triptych: Tiziano Popoli, Pamela Z, Michele Mercure album artworks

Jed Bindeman / Pete Swanson

Triptych: Packaging and formats for FTS014 and FTS015