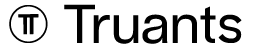

With an overwhelming volume of new music being released weekly, the format that often lends itself best to electronic music – the DJ mix – wrestles against a devaluation that looks to simply reduce it to part of the unrelenting slew of social content artists manage to stay present in today’s scene. London-based DJs 404 Eros (Alex Dique & Theo Fabunmi Stone) are trying to do something different in that sense. The duo’s output reflects more than a simple love of music, instead narrating a deep-seated fascination with the stories, communities and DIY ethos that underpin the genres and sounds most exciting to them. With their projects, they not only intend to spotlight the music they love but also to give a platform to artists and communities that may not have had the recognition they deserve. Their regular radio output on The Lot and NTS explores a rich tapestry of sounds from street soul to lovers rock, boogie and R&B, often focused on a DIY intention: artists who have had to make do with a little and through their limitations have innovated.

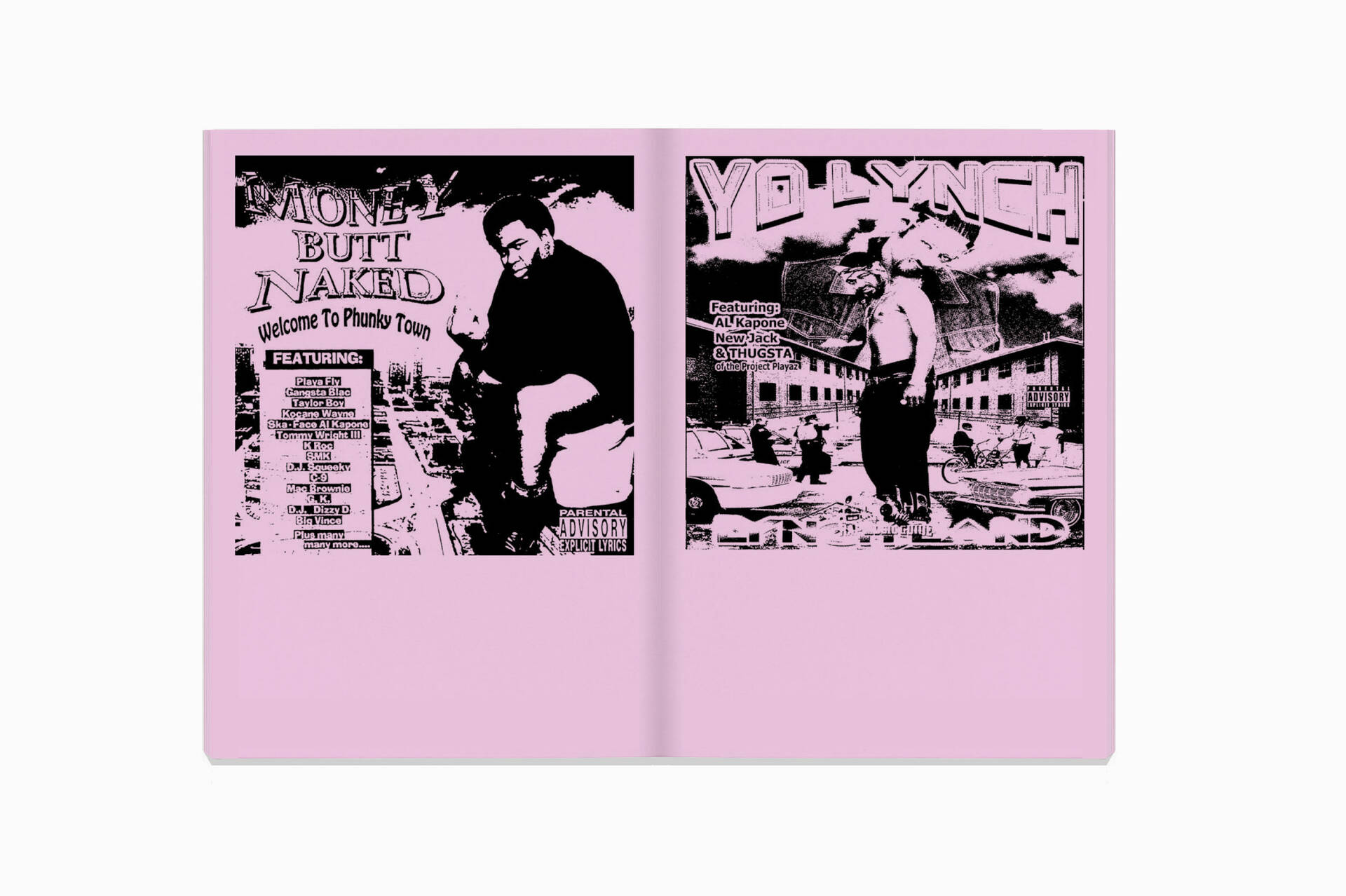

With their latest project, a zine exploring the artwork of Memphis rap, the two curators drew on a different impetus, delving into the visual aesthetics of a genre that never really got its flowers, despite its musical lineage being clearly visible in a lot of popular music today. Originally intended to be a zine that championed some critical artists through interviews, the pair quickly hit a wall trying to penetrate a historically insular and self-sufficient scene. Not wanting to risk any sort of ‘helicopter journalism’ but still intent on paying homage to the music they love, they opted for a different approach, instead looking at the distinctive artwork accompanying the rare rap tapes now circulated online.

The visual aesthetics of Memphis rap are characterised by excess but also rich humour and self-awareness. In some ways, it feels like a prelude to internet memes, with artists presented amongst over-the-top photoshopped explosions, drugs, money and weapons to give a visual flex to the music. The style was characterised by Houston-based design agency Pen & Pixel, however trying to bucket all of the Memphis rap aesthetic under this umbrella doesn’t do it justice. The diversity in visual direction is significant. One of the most exciting things about the genre is that tapes would often come out without any clear artwork or tracklisting, leading to fans creating their own artwork for releases. A single release may have had multiple different covers without any clear official version and reflects the truly community-led nature of this particular rap subgenre.

Truants met 404 Eros to discuss their archival practice and their recent deep dive into Memphis rap. Their entry into the Truancy Volumes series is a snapshot of some of their favourite Memphis selections to accompany their upcoming zine.

You guys don’t do a lot of interviews, but you’ve definitely had a very prolific few years, putting out stuff fairly consistently. What’s the driving force behind the projects you’re putting out? Beyond simple love of the music, there are hints of more intention behind some of the things that you’re covering, and I’m curious about the motivation to focus on certain things over others.

Dique: “Obviously, we love music. That’s a given, lots of people love music. What continues to drive us is being able to tell the story behind where that music came from. In our exploration of various genres, from the Memphis project to street soul, lovers rock to Ethio-jazz, we’ve consistently been drawn to sounds and scenes with a distinctive DIY element that doesn’t come from a ‘traditional’ lineage. Artists creating music in their bedroom, using patched-together instruments or whatever was accessible to them at the time to create a sound that’s unique. Digging into the journey of how that came to fruition, re-discovering the different pieces fell into place and connecting the dots between different scenes still excites me. I also feel that it is important to tell these stories as it’s something that’s often lost with digger culture and the fetishisation of rareness.”

Theo: “The driving factor is first sonically finding something we’re really enjoying, then really geeking out and digging deeper on that, and then seeing where those roots kind of take you. Those people were very much pioneering a specific sound that existed in the community and that existed in clubs, parties, releases, and labels, and so yeah, just trying to reignite what can easily be forgotten.”

“The frustrating part is that you see a lot of labels or people putting themselves at the centre of that story and building a brand around that but what gets missed in the process of that is a contextualising thing, so it’s the aim to contextualise everything and as Alex said these things don’t happen in isolation. They normally happen with a community around them, they happen with limited resources, and that’s where the real creativity comes into play really because you end up trying to use this little Casio synth that everyone’s throwing away because it’s not used for that sound anymore. Still, they find something creative in it, and a lot of ingenuity. So it’s kind of telling the stories of those communities that are often marginalised. I don’t think that’s the driving factor consciously. It’s almost like you find the sound you like, which could be ’80s boogie, and you start going down that rabbit hole. You see Jam and Lewis on production, and you see that they were playing in Prince’s band, you see that they’re from Minnesota or that they’re a part of prolific band members coming from the same school and that’s just crazy. Those are stories that may be easily forgotten. You could equally look at the hip-hop scene in Atlanta, where you’ve got Outkast coming through and those guys going into the Dungeon at the same time as Gnarls Barkley, and those guys are all creating their own unique voice of what is their sound essentially, and it’s the same for Memphis, and it’s the same for street soul. You’ve got all these people, pioneers really, and so easy to forget.”

So that procedure starts with just digging for music and then something triggers the natural curiosity of somebody who loves music and then at some point along the way, when you learn more about that music, you find the things where there isn’t so much out there in terms of contextualisation around this particular genre or this particular thing. So this is where the motivation comes from: to go a bit further, dive a bit deeper, and do that? I always think digging and contextualising is a way of learning and processing as DJs or music fans.

Theo: “Yeah, I don’t think it’s exclusively for DJs. When people enjoy a subject, whether music, food, gardening or whatever, as soon as you start going down the rabbit hole, that’s the fun part of discovery. I think that’s what Memphis was as well. It was super familiar because of the influence on today’s music, for example rhyming in triplets, but it was all new as well at the time when you were going through it, and then maybe there were tracks you knew at a higher level but didn’t know maybe where it sat in its community or even genre-wise really as we didn’t have the context because we weren’t alive when the music came out.”

Dique: “Do you ever have those moments when you’re digging and suddenly recognise a few songs that became popular, or spot a producer you know listed on the liner notes? Leading you down the rabbit hole of ‘what else is out there’ or ‘what’s their story?’ Take Three 6 Mafia, for example; they broke out and popularised the Memphis style of hip-hop, but up until recently that’s where the story stopped for me. Working back from there, diving into the different artists that Three 6 worked with, where the initial sparks of the scene came from (DJ Spanish Fly) and who were the players that didn’t quite get ‘the credit they deserved’. I guess this journey of discovery is what led us down the rabbit hole of Leonard Chin / Santic with lovers rock or Toyin in the world of street soul.”

I wonder if the isolationism and individuality of local scenes are more challenging to achieve these days or if the naivety of doing something not the way it was intended because of how easy it is to see how other people are doing things.

Dique: “I’m not sure if music scenes ever truly evolved in isolation, tempting as it is to romanticise. Scenes and artists have always borrowed, reinvent, and drawn inspiration, shaping their own unique sounds. I’m a Londoner so I’m definitely biased, but perhaps that’s why so much of it flourishes in larger cities. Having access to scenes in far-flung places via the internet or otherwise but doing it their own way isn’t always that negative, in fact the opposite. We’ve been relatively privileged to travel & explore some of these first hand. That being said, it’s important to recognise the privilege, your average musician in Sudan is less likely to have that chance. So yeah, I guess it’s a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it’s a leveller, on the flip, it contributes to the homogenisation of music.”

Theo: “Yeah, maybe where we’re hearing innovative electronic music is in Uganda and Ethiopia and Nyege Nyege, for example. What they’re putting out there, the percussion and the sounds mixed with quite archaic electronics. Nothing else sounds like it. The closest thing is maybe kudoro to an extent but totally its own thing.”

I’m interested in where you’re digging into the narratives that help you better contextualise these musical histories, like Memphis rap. Do you see particular instances or mediums where people provide spaces for these discussions?

Dique: “Yeah, radio, definitely. I’m going back to blogs as well. What’s the name of that hip-hop blog again?”

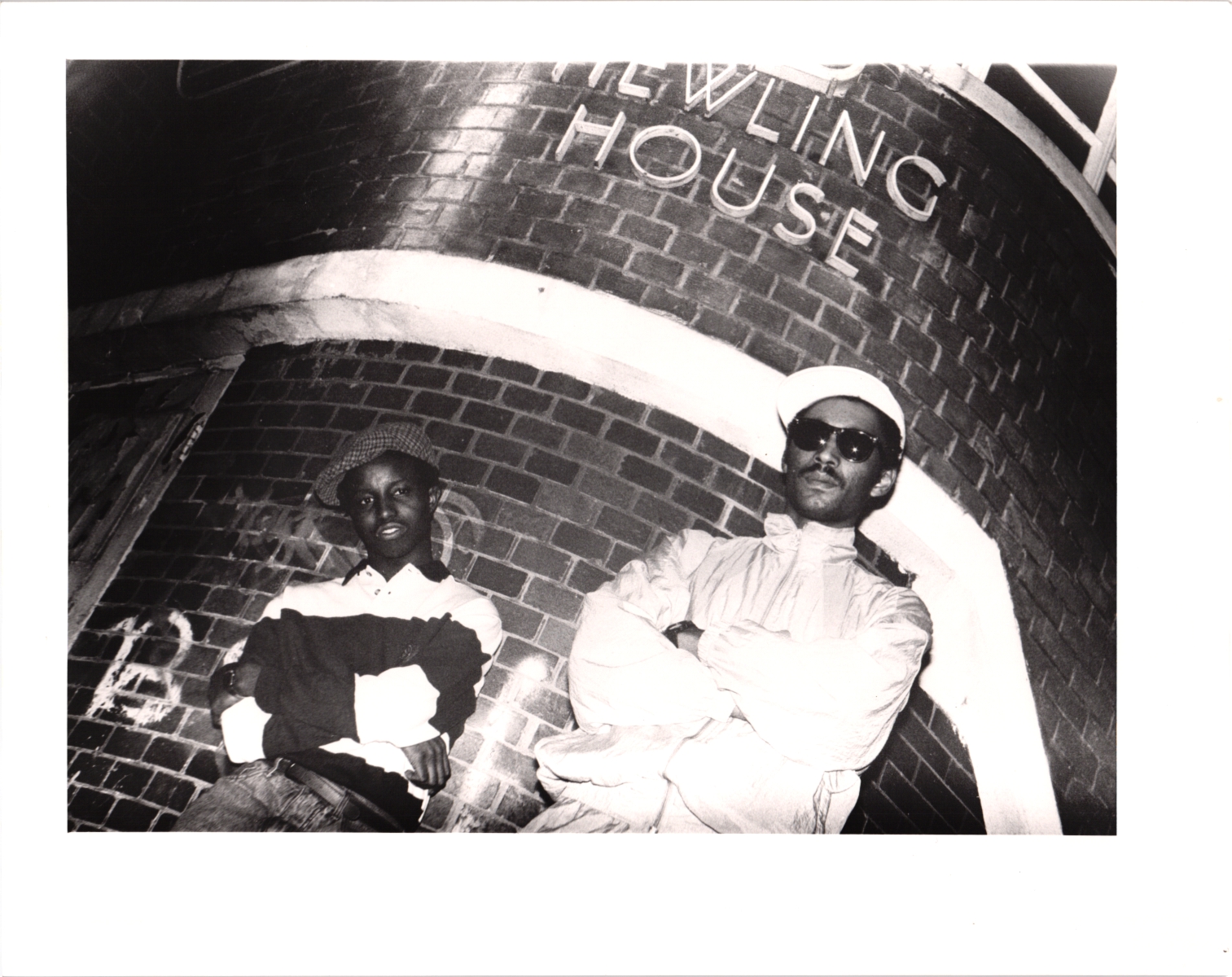

Theo: “Passion Weiss, yeah, they’re good. I think NTS do an excellent job with their shows. I think physical spaces should be something that celebrates those things. I think where the UK is, in terms of funding, it’s obviously not getting funding and very deprioritised. I’m not sure if I’ve mentioned this before, but there was this event related to the Toyin Agbetu project we did for RA, the street soul thing. I came across an exhibition celebrating a publication and platform that existed, that happened in a Clapton social centre or library. The community of people who worked there would offer literary classes to immigrants and ensure the library was stocked with POC and non-Western literature. He and his wife were a prominent part of that community, and I just saw his name everywhere, and I was like, I know his name from records, it’s kind of crazy how much he’s about. So yeah, for me, I’m sure I’m not the only person who learned something from going to that space on that day. I think this can make a big difference. You also just have to dig deep too. Try and find some old outdated, dial-up-esque-looking website to find things. We had some Memphis blogs that we would go to that were still very active.”

I was browsing Reddit a little bit in the run-up to this interview, and some guy was chatting about the Money Butt Naked artwork where he’s sitting on the toilet. It turned out this person happened to be an OG of the scene who had worked on many releases and knew a lot, and he was just hanging out, passing on stories about old releases. I think because some of these histories haven’t been talked about much, custodians are often willing to disseminate that information through these platforms.

Dique: “There are two guys who are behind a massive amount of the ’90s Memphis rap artwork, Pen & Pixel.”

Theo: “They were asked to do 21 Savage’s last album, and I think it’s interesting that they were kind of heralded as the designers for that stuff, and that could have easily gotten lost if there wasn’t a reference from the last few years pointing back to it. The heads will know, but the fact it’s on a platform of someone as big as 21 Savage you really appreciate an artist for doing something that nods to it.”

We’ll talk about Pen & Pixel in a second, but maybe you can explain how this specific project came about and how it evolved, as you originally had a slightly different approach or intention.

Dique: “What reignited my interest were a couple of reissues. The first came from Delroy Edwards’ label, LA Club Resource. It featured releases by Lil Noid, 2 Low Key, and Shawty Pimp etc. Listening to the sound for the first time, diving into it, rediscovering the Three 6 Mafia bits I had heard years ago, and then delving into the different stories through blogs or YouTube. Finding out more about the early origins of Memphis hip-hop with artists like DJ Spanish Fly, who essentially pioneered the sound. He combined rap vocals with electro/house beats that morphed into a sound of its own, using equipment not necessarily made for ‘hip-hop’. Somehow, he made it work, inspiring a scene in the process. Initially we wanted to run a few interviews with artists from the time but this proved to be pretty challenging. Conscious we’re not from Memphis, we’re relative outsiders and wouldn’t want to come across as helicopter journalists – so we settled on paying homage through a mix and zine of the artworks.”

Theo: “Yeah, we tried. I feel like it wasn’t through a lack of trying. We got in contact with some of the artists and had some interesting conversations with people who grew up in or adjacent to Memphis, so they were able to give us some additional context about what that music meant to the broader community. In terms of people contributing to it though, we struggled to find people who were willing to have a conversation, so from a storytelling perspective, we thought we’d take a more visual approach and just kind of catalogue some of our favourite artworks that we feel represent what we like about the scene.”

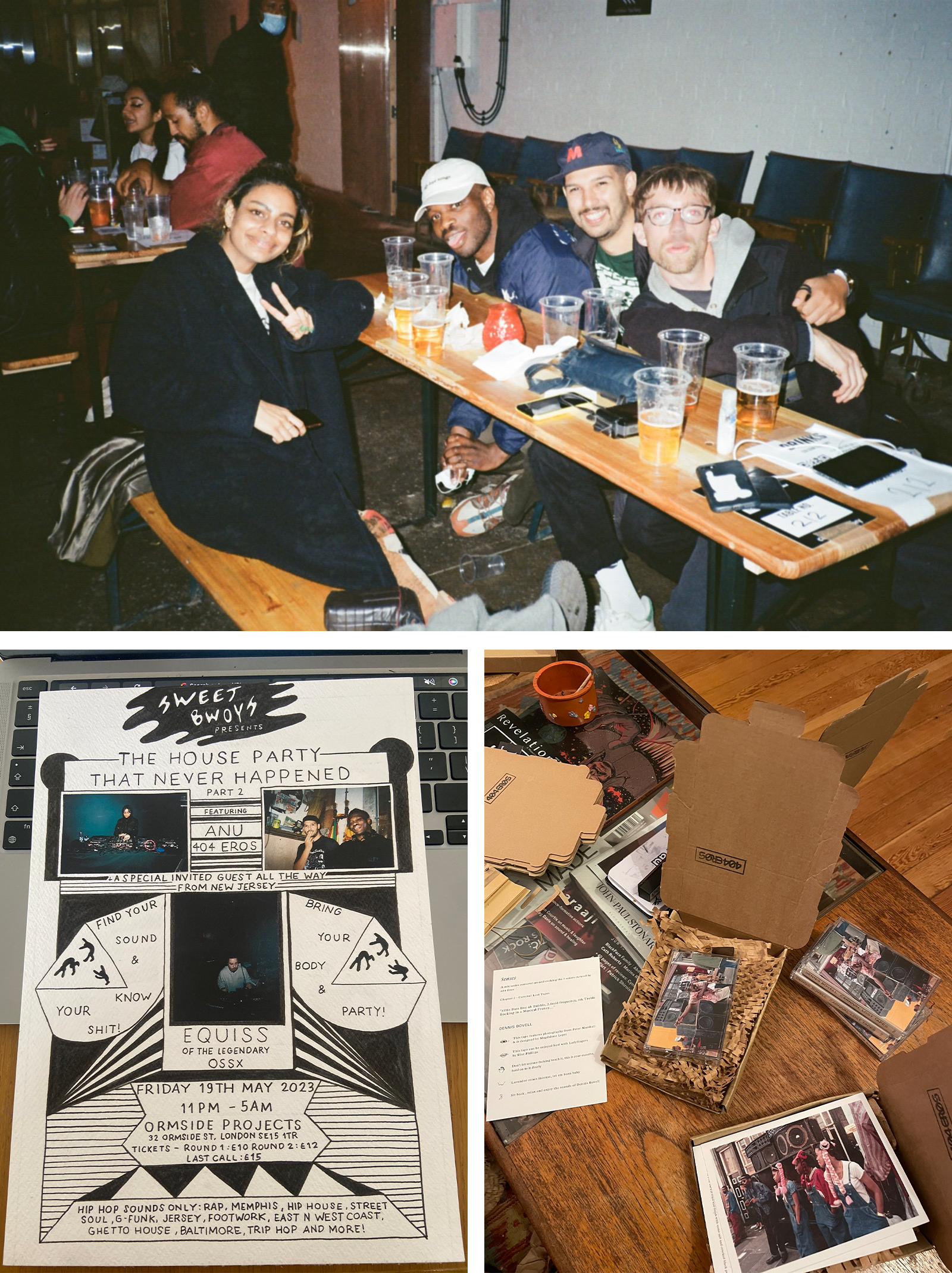

“To add to what Alex was saying earlier, I was a bit more aware of Memphis earlier, but not in the way we are now aware. I’d say that I knew Three 6 Mafia for example, who they were, but I didn’t know it existed as a wider community and music scene. They won a Grammy for Hustle and Flow, so they were like, elevated, special, and so I’ve known them but I didn’t know what existed beyond them, really. I think maybe during COVID, club music just made a lot less sense at that time, and during that period, we kind of doubled down on the music that we love, and hip-hop is a large part of that. Those conversations brought about Sweet Bwoyz with Anu because we were all just listening to hip-hop. Anu kind of went one direction of listening to a lot of Japanese hip-hop and a lot of like, boom bap stuff from the ’80s and ’90s, and we kind of just went down hard on the Memphis stuff. Then it became how do we tell this story and as it became more of a struggle to do the interview process, the mix and the visual aspect made sense.”

Can you tell us a bit more about Sweet Bwoyz?

Theo: “Yeah, that kind of came from us thinking that it would be cool if there was a hip-hop night that wasn’t just like playing Drake, basically. We wanted a hip-hop night playing hip-hop we like because that’s the problem. If you’re looking for a hip-hop night in London, or someone’s like, coming over and wanting to check out a hip-hop night in London, you have to caveat it with what kind of hip-hop you want to hear. I can’t think of many nights that have a whole night dedicated to the hip-hop that we’re playing at these parties rather than the odd song. I can’t think of many hip-hop sets I’ve heard in an electronic club space.”

Dique: “Yeah, for sure.”

Theo: “I should add that hip-hop music is electronic music because some people feel that’s not the case. It becomes very frustrating when you’re talking to venues about doing a hip-hop night, and they’re like, we only cater to electronic music because hip-hop is electronic music.”

So I think this is the first project where you’ve come at it from a visual perspective. You’ve released other projects where the music shapes it or the 5enses project that incorporates other elements like scent, but from a visual perspective, what was the curatorial approach like? How did you pick the artwork you wanted to include?

Theo: “We are both obviously massive fans of the artwork, but we should probably mention that it was a close friend of ours, Asel, who’s an amazing designer, who said we should probably do a zine on this. We were telling them that we were struggling to get it done the way we wanted to, so that was a suggestion from their side. They’re also working on this, but it’s definitely led from our side regarding the curation and what we wanted to include based on our knowledge or understanding of the music and the artists. It was what’s most visually compelling, but then of course we couldn’t leave out Tommy Wright III, right?”

The influence of Pen & Pixel is very prominent, but the artwork also has a diversity of styles. Sometimes you see more hand-drawn stuff, sometimes, there are more or less overlays, and there are different categories of artwork, even within the space.

Theo: “Definitely. Some of it is more photo-driven, some is more illustrative, or you have like, the Lil Gin artwork, which is definitely inspired by Blaxploitation kind of movies, which Pen & Pixel maybe wouldn’t have had that strong a reference for. The other thing is that because they’re so close to the Bible Belt, there are lots of references to the Church and also quite demonic references coming from the fact that the state is so religious. So yeah, there’s definitely a lot of distinctions, subgenres and varying visual elements.”

Dique: “It’s satanic almost with references to the supernatural, interwoven into the artwork. When we were talking to Imakemadbeats, he was very much like, ‘we’re in the Bible Belt’, and this was a rejection of mainstream society from a people that have been marginalised to a large extent.”

What I find interesting about this, and at least what I’ve read, is that many mixtapes would come out without artwork, without a tracklisting, so fans would create their own art for the release. Many releases had a few versions of the cover art, creating this kind of interesting community-driven feeling around the music and the scene.

Dique: “Yeah, it’s a product of this community-led approach we referenced earlier.”

It’s also funny that that kind of Pen & Pixel style of artwork almost feels like early meme culture. Some of this artwork is extravagant, and everything is blown up and over the top with the references. It’s sort of a flex but also very self-aware.

Theo: “100%. It’s worth mentioning that like a lot of this music was documented during the crack epidemic in the United States. A lot of the music is glamourising conditions of the ghetto really. Still, at the same time, these people are in these situations and trying to navigate how to exist in a country that’s ignored them and left them to survive, and they’ve found an interesting and exciting way of telling their story.”

Dique: “The lyrics and the themes are always quite raw and visceral, and come from a reality of the time, right?”

Theo: “Hard not to think of Young Thug, kinda crazy if you think about how courts are trying to use lyrics as evidence these days. Well yeah, these guys were being very specific about where they shot, robbed or killed someone. It was a different time but maybe also a reflection of how underground the scene was.”

You’ve put a mix together for us. Can you tell us a little bit about it and the process?

Theo: “We both had very long playlists on YouTube, which we shared and then I ended up recording a version and the intention wasn’t doing a mix yet, I was just having fun, but Alex said it didn’t sound too bad. So we did it properly, just putting some tunes we liked together. What we didn’t want is it to feel like an anthology on Memphis, because it’s not. There’s definitely stuff missed, and like any mix, there are always tracks you like that don’t really fit. One track we tried to get in was this Princess Loko track because she passed away during COVID but it just didn’t work. We end it on Spanish Fly with this feeling of him being the godfather of Memphis, but funnily enough, that wasn’t actually in the tracklist. We were finishing up, and I saw there was one track left and it was that, and it just worked well.”

Dique: “That’s the process for most of our mixes. We’ll probably be digging for years and revisiting the tracks we found. Then, the most challenging thing is not just putting all of your favourite tracks in there but also working out what will mix and what gives it a little space to breathe. You can be your own worst enemy too. I don’t think we’ll ever get over our insecurities or anxieties when putting a mix together.”

Theo: “Quality is always an issue with Memphis stuff, too. You just won’t find a high-quality version of some of that stuff.”

Do you want to discuss anything else you guys have coming up or anything else you want to push?

Dique: “We’ve been working on our 5enses cassette series for around three years now. It was born from the pandemic, at a similar time to when we first started discussing this Memphis project. Each chapter has been used to document a period. The most recent one we’ve released over the last year was based around Carnival and what that means to the artists involved. We put the mixes out on cassette and they’re accompanied with articles that represent the other senses. In addition to the artists (Lord Tusk, Dennis Bovell, Equiknoxx and Zakia, to name a few), it’s been great working with visual artists and photographers, and recipe developers and chefs (shouts to Ixta Belfrage and Riaz). Next chapter to be released this year, where we’ll be focusing on the theme: Normalise The Crush.”

“We’ll also be doing a few more in-focuses on different scenes we’ve taken an interest in. What form that takes is to be seen. Outside of that we’ll be playing over the summer at Rally Festival and We Out Here, plus a few gigs dotted around town – including our next Sweet Bwoyz party on April 20th.”

404 Eros: Soundcloud, Bandcamp, Instagram, Resident Advisor

Their zine exploring the artwork of Memphis rap is available now here.

Interview by Mike Evans

You can download Truancy Volume 326: 404 Eros in 320 kbps here. No tracklist for this one but if any readers would like to help put one together please head over to our Soundcloud link with your finds. Your support helps cover all our costs and allows Truants to continue running as a non-profit and ad-free platform. Members will receive exclusive access to mixes, tracklists, and discounts off future merchandise. We urge you to support the future of independent music journalism—a little goes a long way.