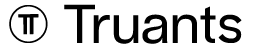

In a musical landscape where production often leans toward formula, Time Cow moves with deliberate purpose, simultaneously honoring and reimagining Jamaica’s rich musical heritage. As a core member of Equiknoxx, he helped introduce the world to Kingston’s experimental dancehall scene, but his solo work reveals an artist operating with even greater conceptual freedom—methodically deconstructing tradition before reassembling something vibrant and unexpected.

His recent outputs on his own Kullijhan Records illuminate this approach with startling clarity. Million Leg Millipede evokes the feeling of tramping through a lush island rainforest by night, while Scaring 1100 Chickens To Death ventures into territory familiar to DDS devotees and Hard Wax patrons alike, balancing mechanical precision with organic warmth. This balance stems from Time Cow’s unique position within Jamaican music culture. Coming of age in a scene where groundbreaking sounds emerge rapidly but aren’t always documented internationally, he deliberately weaves dancehall and reggae into broader electronic contexts, highlighting connections often overlooked in dance music conversations.

His Truancy Volume embodies this philosophy with sultry magnetism and kinetic energy. The journey begins with Lalah Hathaway’s honeyed tones before erupting into the feverish intensity of Merciless and Bucaneer’s ’90s dancehall classics. From there, Time Cow crafts a mesmerizing narrative across decades and genres—Taxi Gang’s shimmering reggae interpretation of Beethoven’s 5th sits alongside frenetic bass explorations, while his edit of Genesis’ “Tonight Tonight” (playfully nodding to his theory that “Phil Collins invented Amapiano”) transitions into contemporary club territories. Throughout the mix, he creates combustible connections between seemingly disparate worlds: Peter Tosh’s sun-kissed reggae-disco hybrid “Dubbing Buk-In-Hamm” flows into Gwen Guthrie’s Larry Levan-remixed velvet house classic, while Equiknoxx’s own remix of Fever Ray dissolves into hallucinogenic electronic textures. French Caribbean music and Bouyon genres make deliberate appearances, showcasing what Time Cow values as “sonically clean and heavy” music where women’s voices prominently feature.

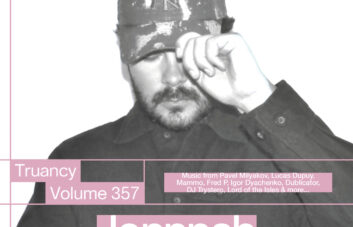

Beyond music, Time Cow’s creative perspective is informed by his passion for cooking and photography. He approaches these disciplines with the same restless experimentation that defines his production work, discovering that creative explorations in one field often catalyze breakthroughs in another. This cross-pollination manifests in music that feels alive with possibility—simultaneously technical and intuitive, structured and free-flowing. With upcoming projects spanning proto-jazz collaborations and electronic productions designed for emerging talents, Time Cow continues building bridges between tradition and innovation, always with an eye toward evolving Jamaican music’s global position through both artistic integrity and constructive industry relationships.

Hi, Time Cow! Thank you so much for recording this mix for TRUANTS. How are you and what have you been up to lately? “I’m doing okay! I’ve been at home with family and friends; finishing up projects and becoming more active in music again.”

You’ve mentioned how Jamaica has this unique position where musical innovations happen rapidly but aren’t always documented or celebrated internationally. How does this dynamic influence your approach to preserving and evolving Jamaican musical traditions? “By name and nature Dancehall is dance music, and it’s often left out of that conversation. When putting together a mix, I try to weave into the tapestry of dance music as much dancehall and reggae as context allows. When I play to a live audience I’m sure to include the seminal dancehall and reggae hits to get younger persons familiar and to satisfy those for whom these songs were an essential part of their earlier raving days.”

Your production style has this remarkable ability to simultaneously honor dancehall’s roots while pushing its boundaries. When you’re creating, how conscious are you of this balance between tradition and innovation? “I’m wholly conscious of trying to strike a balance. I’m aware of the influences and spawns of the many genres of Jamaica and when creating I subconsciously make justifications for sometimes borrowing and charting new territory.

The journey from those early Equiknoxx days to your recent solo releases like Million Leg Millipede reflects significant artistic evolution. What key moments or realizations shaped your growth as a producer? “The sum of my earlier years as a a teenager was making music with friends which taught me how dynamic and fun music had to be to make sense for me. Following that was being under the wings of persons who had attained some mastery of the craft, who guided me; most notably and with the longest relationship, Gavin. Then, touring for the first time under the Equinoxx Music banner with Gavin and Shanique which was a swift broadening of the horizon, being exposed to cultures and art from many places and people. The last crucial moment was around the start of COVID when I forced myself off the crutches of sample based production and took the time to learn other ways.”

You’ve had unique collaborations across your career, from fellow Equiknoxx members to artists like SO$A and RTKAL. How do these different collaborative dynamics influence your creative approach? “Collaboration is at the heart of music making, especially if you intend to make your music work and/or make music your work. A single track can be defined by many relationships and processes and that’s the way I started, in an environment of friendship and work. Each artist has their own sound, ideas and personalities and it’s up to the producer to find where the relationship works and get the best results. Working with a lot of people only helps to sharpen the abilities of all parties involved so I like when its dynamic.”

Starting Kullijhan Records represents a new chapter in your musical journey. What artistic freedom has having your own label platform provided? “It was actually started in high school with a few friends, but 2024 is the year I decided I needed to do something to command that artistic freedom. The releases currently available from Kullijhan Records are diverse from release to release and I would like to keep things that way as a documentation of what is possible from Jamaica, from friends, under one roof from my own vision.”

Between Kingston, London, Berlin and beyond—how do these different musical environments feed into your creative process? Has the international reception of your music shifted your perspective on Jamaica’s place in global electronic music? “In our downtime on tour, we link with friends, have food, see the sights, get a feel of the place and try to understand, in context, the music that comes from that particular place. That kind of observation and conversation with the people and the place informs and guides what I do to understand who may like a particular track, where it may be well received, what tempo will work best for what track, etc. The reception to the music is really a testament to the groundwork of the forefathers of Jamaican music and the diaspora who were instrumental in setting up shop, setting a stage for all the sounds and styles to be adopted and blended into present day music.”

Your music often employs fascinating textural contrasts—digital precision alongside organic elements, structured patterns with unexpected disruptions. What’s your process for discovering and developing these unique sonic textures? “Well the digital precision most likely is a result of the tools used and my own personality. Sometimes my music has a little less swing than most Dancehall fans are used to. It’s fairly common knowledge a lot of Dancehall pioneers used the MPC. Sly and Robbie, Lenky Marsden, and Jeremy Harding all used the MPC and there’s a noticeable swing when you program with the MPC. Starting with computers I was anal about getting the parameters as tight as possible because that looked pleasant to the eye; not so much recently though; I’ve learned to be free. My discovery process is one part organic and one part academic. There’s times I will watch a lot of Westerns and I search for the music and on that search I discover common themes and approaches musicians use. When Sergio Leone teams up with Ennio Morricone; I have an expectation of what the music will be like. Ennio uses the voice as an instrument; sometimes hums and whistles, sometimes made up words used in a sequence to create a refrain. There’s periods of times that I browse still functional blogspots and check the uploads for sample material that I sit and listen through which has added to my knowledge of what’s out there.”

Beyond the technical aspects of production, what emotional qualities or experiences are you trying to capture in your music? “I’m trying to be all encompassing; to express that which sometimes words cannot. There’s releases I have planned to cover the spectrum. I dare say in the next 5-10 years someone can go through my catalogue and find at least one song that touches them.”

The title “Scaring 1100 Chickens To Death” conjures such vivid imagery. How do narrative and storytelling elements factor into your approach to production and track naming? “This title was a real event and conjures up vivid imagery that is not available with the original news story. It is the result of life experiences, events and anecdotes which gives birth to some of the track titles. Who cleans the chalice straw is an obvious one because you’ll be looking at a group of smokers puffing the chalice and think well that pipe must get dirty at some point.”

Jamaica has profoundly shaped global music culture, yet Jamaican artists are often underrepresented in international electronic scenes. What perspectives or elements do you feel are important to bring forward in your work? “For me the work is not only the musical work but also more positive interactions within the industry. On the musical side I want to do my own part to improve production values; higher quality recordings, less muddy mixes, and more impactful arrangements. These are sore points for me in recent times listening to music from Jamaica. On the interactions side there’s countless stories of opportunities that fall through or just completely stopped because of a negative interaction with a Jamaican person; whether the person was homophobic, transphobic, rude, late, etc. and I would like to change that perception.”

Your diverse musical references span from traditional Jamaican forms to experimental electronics. Are there any unexpected influences that people might be surprised have shaped your sound? “This is probably hardest to answer because I listen to almost anything that sounds interesting and try to seek out more of it if it like it. I’ll listen anywhere from Andre Popp to Momoko Kikuchi and back to Archie Shepp.”

Your social media often shows glimpses of your passion for cooking and photography alongside your musical work. How do these different forms of creative expression nurture different aspects of your creativity? “All the world is art and passion, even the mundane. One day frying chicken you might decide to add some nutmeg powder to the flour and you discover another dimension of taste. The same happens with photography; you might dislike the 50mm for things outside its intended portraiture photography but it does capture frogs and lizards up close well. All those experiments and experiences in all the things we do inform and assist our passions and let us know more is possible.”

What brings you the most joy in your creative process right now? “I’ve just really been able to afford outboard gear in pursuance of higher production values and learning hands on really gets me excited.”

What was your approach to crafting your Truancy Volume mix, and are there any particular tracks that hold special significance for you? “Different tracks have different places in my heart and I’ve tried to paint a picture with them. One thing you quickly realise with dancehall tracks is the pacing of them will force you to move on to another similar track to keep that high energy going so I tried to get all that energy out early with ‘Buccaneer – Bruk Out Rancid Rock Mix’. I was recently listening to Genesis’ ‘Tonight Tonight’ and joked around that Phil Collins invented Amapiano so I had to dive into my conspiracy there. I went back to Jamaican produced house and club music with the Gwen Guthrie tune produced by Sly and Robbie. There’s a few special edits in there and songs from different parts of the Caribbean. French Caribbean music and genres like Bouyon had to be included because to me the sound is sonically clean and heavy. It makes you want to dance, and theres so many women present and making the music it doesn’t feel as anxiety/rage inducing as current dancehall.”

Looking ahead, what territories—musical or otherwise—are you eager to explore in your upcoming work? What are you looking forward to most in the coming months? “I’m trying to finish up a proto-jazz album with a few friends which is as dynamic as it gets and it’s really given me the opportunity to get a few unlikely pairings together. I’ve also got another electronic drum project prepared that I have a special mission for to get fledgling producers and DJ’s involved.”

Time Cow: Bandcamp, Instagram, Kullijhan Records, Linktree, NTS, Soundcloud, X [Twitter]

You can download Truancy Volume 347: Time Cow in 320 kbps and view the full tracklist on Patreon here. Your support helps cover all our costs and allows Truants to continue running as a non-profit and ad-free platform. Members will receive exclusive access to mixes and tracklists. We urge you to support the future of independent music journalism—a little goes a long way. If you need any IDs though, please leave us a comment on the Soundcloud link and us or Time Cow will get back to you with the track :)